From SSTI to SSTI to RCE - Bypassing Thymeleaf sandbox <= 3.1.3.RELEASE

Abstract The Thymeleaf release version 3.0.12 came with improvements in its sandboxed evaluation process, by restricting objects creations and static functio...

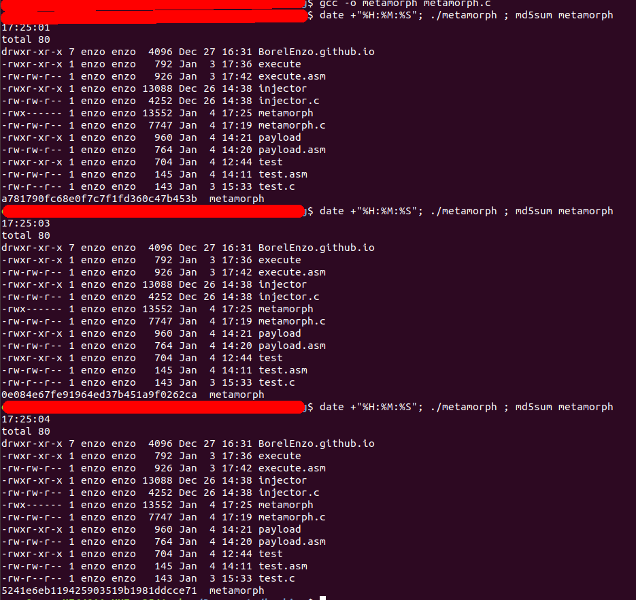

In the previous article, I described how I wrote a simple polymorphic program. “Polymorphic” means that the program (the binary) changes its appearance every time (the md5 sum was indeed different), but the behavior was always the same. The payload was always decrypted to the same shellcode, and therefore, a malware using this technique to hide its malicious content would be easily detected, as it could be trivial to create a signature from the decrypted payload.

Metamorphic programs are more difficult to write, but can be way more difficult to detect. Whereas polymorphic program contain a decrypted code which is essentially the same every time, metamorphic programs can “re-code” themselves. The general behavior will be the normally the same, but the shellcode, and possibly the rest of the program will be different. How is it possible ?

The idea is to make the code flexible:

Besides the malicious code, we have therefore to write a bunch of routines (the morphing engine), becoming more and more complex as the malicious code becomes harder to detect.

For this first article on this topic, we propose a simple metamorphic program able to reorder its instructions and shuffle them for the next execution.

Hereafter, we will use the following terms:

Let’s imagine that we have the following shellcode ( jmp $+2 does nothing but jumping to the next instruction ):

jmp $+2 push rdi ;i1 jmp $+2 push rsi ;i2 jmp $+2 push rdx ;i3 jmp $+2 push rax ;i4 jmp $+2 ...

and we shuffle it in this way (and recompute distances):

jmp $+5 push rdx ;i3 jmp $+5 push rdi ;i1 jmp $+5 push rax ;i4 jmp $+5 push rsi ;i2 jmp $-10 ...

If we are currently executing i1, the “next instruction in the shellcode” is i4, but the “next instruction to execute is i2 (in the non-shuffled version, the “next instruction”’s are the same).

The goal of the program we wrote was to execute “/bin/ls -l”. The difficulty here is to write a shellcode such that none of the operands is expressed relatively to $rip because of the shuffling. It means

that we cannot put the constant strings at the end of the shellcode or in the .data section. The shellcode is as follows:

section .text global _start _start: push rdx ; save rdx push rdi ; save rdi push rsi ; save rsi push 0x006c2d ; push "-l" push 0x736c2f ; push "/ls" sub rsp, 4 ; don't use push here mov dword [rsp], 0x6e69622f ;move "/bin" onto the stack push 0x0 ; push null element lea rdi, [rsp+20] ; rdi = address of the argument push rdi ; push it lea rdi, [rsp+16] ; rdi = address of the command push rdi ; push it mov rsi, rsp ; rsi = @[@"/bin/ls", @"-l" ] mov rdx, 0x0 ; NULL mov rax, 0x3b ; execve syscall add rsp, 44 ; restore stack pointer syscall pop rsi ; restore rsi pop rdi ; restore rdi pop rdx ; restore rdx

The register $rsi contains the address of an array containing the addresses of the command and its parameters, here: [@”/bin/ls”, @”-l”]. That’s the reason why we put the addresses of these strings

(instructions 10 and 12). The string “/bin/ls” cannot be pushed as an int, that’s the reason why we do it in two times, and manually modify $rsp.

To make it flexible, we simply have to put jmp $+2 between instructions ( jmp $+2 is translated into eb 00, which is a null jump):

section .text global _start _start: jmp $+2 push rdx ; save rdx jmp $+2 push rdi ; save rdi jmp $+2 push rsi ; save rsi jmp $+2 push 0x006c2d ; push "-l" jmp $+2 push 0x736c2f ; push "/ls" jmp $+2 sub rsp, 4 ; don't use push here jmp $+2 mov dword [rsp], 0x6e69622f ;move "/bin" onto the stack jmp $+2 push 0x0 ; push null element jmp $+2 lea rdi, [rsp+20] ; rdi = address of the argument jmp $+2 push rdi ; push it jmp $+2 lea rdi, [rsp+16] ; rdi = address of the command jmp $+2 push rdi ; push it jmp $+2 mov rsi, rsp ; rsi = @[@"/bin/ls", @"-l" ] jmp $+2 mov rdx, 0x0 ; NULL jmp $+2 mov rax, 0x3b ; execve syscall jmp $+2 add rsp, 44 ; restore stack pointer jmp $+2 syscall jmp $+2 pop rsi ; restore rsi jmp $+2 pop rdi ; restore rdi jmp $+2 pop rdx ; restore rdx jmp $+2

It’s important to have a leading and a trailing JMP, because once the shellcode is shuffled, we have to reach the first useful instruction at the beginning, and the next instruction to execute as we reach the last instruction of the shellcode.

The following imports are required:

#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <sys/stat.h> #include <fcntl.h> #include <unistd.h> #include <string.h> #include <time.h> #include <elf.h> #include <sys/mman.h>

The shellcode is 102-bytes long and is not shuffled as we write the program. It is stored in a global static variable because we want it in the .data section. Since we will not use string’s function,

we can ignore the trailing null-byte:

#define SHELLCODE_SIZE 102 static unsigned char shellcode[SHELLCODE_SIZE] = "\xeb\x00R\xeb\x00W\xeb\x00V\xeb\x00h-l\x00\x00\xeb\x00h/ls\x00\xeb\x00H\x83\xec\x04\xeb\x00\xc7\x04$/bin\xeb\x00j\x00\xeb\x00H\x8d|$\x14\xeb\x00W\xeb\x00H\x8d|$\x10\xeb\x00W\xeb\x00H\x89\xe6\xeb\x00\xba\x00\x00\x00\x00\xeb\x00\xb8;\x00\x00\x00\xeb\x00H\x83\xc4,\xeb\x00\x0f\x05\xeb\x00^\xeb\x00_\xeb\x00Z\xeb\x00";

We use the following structure to store the shellcode instructions:

typedef struct Instr_struct{ char* i_code; //shellcode "chunk". Points somewhere in the string $shellcode char i_code_len; //length of the instruction char i_index; //execution index char i_jump; //jump to reach next instruction } Instr;

The program will overwrite itself, and therefore, the variable shellcode will contain a different string every time, ready to be executed. The structure Instr will only help us to shuffle and compute

the jumps.

The main routine is quite simple. First, the program will read its own binary content. Then, the routine mutate is called and magic happens inside. The variable data is modified in the routine,

so that what corresponds to the .data section in data contains, after executing mutate, the new shellcode. The binary of the running program is then replaced by a file having the same name and finally, the shellcode

is executed, after granting the execution permission to the memory page.

int main(int argc, char** argv){ char* data; struct stat info; int fd; /** Reads itself **/ if ((fd = open(argv[0], O_RDONLY, 0)) < 0) die(NULL, "Could not read myself\n"); fstat(fd, &info); if (!(data = malloc(info.st_size))) die(data, "Could not allocate memory\n"); read(fd, data, info.st_size); close(fd); mutate(data); /** Overwrites itself **/ if (unlink(argv[0]) < 0) die(data, "Could not unlink myself\n"); if ((fd = open(argv[0], O_CREAT|O_TRUNC|O_RDWR, S_IRWXU)) < 0) die(data, "Could not re-create myself\n"); if (write(fd, data, info.st_size) < 0) die(data, "Could not re-write myself\n"); close(fd); free(data); /** Execute shellcode **/ uintptr_t pagestart = (uintptr_t)shellcode & -getpagesize(); if (mprotect((void*)pagestart, ((uintptr_t)shellcode + SHELLCODE_SIZE - pagestart), PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE | PROT_EXEC) < 0) die(data, "Could not change permissions before executing. Exiting\n"); ((void(*)())shellcode)(); } void die(char* p_data, char* p_msg){ if (p_data) free(p_data); fprintf(stderr, p_msg, NULL); exit(EXIT_FAILURE); }

The die routine is used only for debugging purpose, as it simply prints a message, eventually frees the dynamically allocated buffer and exits.

The routine mutate is the most complicated, that’s the reason why some helpers have been written to make it easier to understand. The first one is based on the one given here

or the one we used in the previous article. It reads the data as an ELF header and finds the offset of the .data section.

Elf64_Shdr* get_section(void* p_data){ int i; Elf64_Ehdr* elf_header = (Elf64_Ehdr*) p_data; Elf64_Shdr* section_header_table = (Elf64_Shdr*) (p_data + elf_header->e_shoff); char* strtab_ptr = p_data + section_header_table[elf_header->e_shstrndx].sh_offset; for (i = 0; i < elf_header->e_shnum; i++){ if (!strcmp(strtab_ptr + section_header_table[i].sh_name, ".data")) return §ion_header_table[i]; } return NULL; }

We also created a routine named split_instructions, which … splits instructions, and returns a pointer to an array of Instr’s pointers:

Instr** split_instructions(char* p_data, int p_nb_instrs){ Instr** instrs = malloc(p_nb_instrs * sizeof(Instr*)); int i, j; unsigned char k; for (i = 0; i < p_nb_instrs; i++){ instrs[i] = malloc(sizeof(Instr)); } j = shellcode[1] + 2; //first opcode after initial jump: shellcode[1] is the distance and +2 is for the jmp instruction itself for(i = 0; i < p_nb_instrs; i++){ k = j + 1; //second char of next instruction while (k < SHELLCODE_SIZE && shellcode[k] != 0xeb) k++; //now, k = next jmp /** Next jump has been found. Shellcode[j+1:k] is an instruction **/ instrs[i]->i_code_len = k - j; instrs[i]->i_code = &shellcode[j]; instrs[i]->i_index = i; instrs[i]->i_jump = (char)shellcode[k + 1]; j = k + instrs[i]->i_jump + 2 ; //jumps to next instruction TO EXECUTE } return instrs; }

It takes two arguments: the first one if the binay file data read in main, and the second one is the number of instructions (detailed later). It begins by dynamically allocating memory and set j = shellcode[1]+2.

If we look at the shellcode, we can see the second byte contains a 0x00 at the beginning and is actually the distance between the current JMP and the first instruction to execute. We add 2 to this value

because we have to take into account the current JMP (the 1st one) which is 2-bytes long. At this moment, j points to the first opcode of an useful instruction. The variable k is set to j+1 and is incremented

until reaching the next JMP (0xeb opcode). The difference between j and k is the length of the code of the useful instruction, and j is the address of the code of the instruction starts.

The variable i is used to set the attribute i_ index, used later during the shuffling. Since we pass from one instruction to another by using JMPs, their indexes in the list are the same as the i_index. Finally,

since k points to the 0xeb after instruction’s code, the next offset is at k+1. The next j is then given by adding the current k, the relative jump and the length of a JMP.

The goal of the mutation routine is to walk through the shuffled code, shuffle it once again, and recompute jumps. The first thing to do is to count how many instructions we have, according to the number of JMPs (reminder: there is one JMP more):

void mutate(char* p_data){ int nb_instr = 0, i, j; unsigned char count; char* cursor = malloc(SHELLCODE_SIZE); Instr* instr = NULL; /** Count how many jumps there are **/ for (i = 0; i < SHELLCODE_SIZE; i++){ if (shellcode[i] == 0xeb) nb_instr++; } nb_instr--; //instrs: array containing all "useful" instructions, in the right order Instr** instrs = split_instructions(p_data, nb_instr); ...

Once we have the list instrs with instructions stored according to the execution order (their index i in the list is the same as their attribute i_index ), we want to shuffle the list. However, we need

to have a way to know where is stored the next instruction to execute, for each instruction. This is done by creating the array instrs_idx:

... /** Shuffle **/ int instrs_idx[nb_instr]; for (i = 0; i < nb_instr; i++) instrs_idx[i] = i; ...

It’s now time to shuffle the array and update instrs_idx to be able to know where is stored the pointer of the i-th instruction in instrs.

We are still in mutate, juste after the previous snippet. The while condition will be detailed later. The idea here is to swap pointers in instrs, and update instrs_idx properly.

... srand(time(NULL)); do{ for (i = 0; i < nb_instr -1; i++) { j = i + rand() / (RAND_MAX / (nb_instr - i) + 1); //swap instructions instr = instrs[i]; instrs[i] = instrs[j]; instrs[j] = instr; //swap the indexes, but according to the i_index! int idx = instrs_idx[instrs[i]->i_index]; instrs_idx[instrs[i]->i_index] = instrs_idx[instrs[j]->i_index]; instrs_idx[instrs[j]->i_index] = idx; } } while((count = set_jumps(instrs, instrs_idx, nb_instr)) == 0xff); //if all offsets are okay, continue ...

We cannot simply swap indexes in instrs_idx, because it would be totally wrong. Let’s take an example.

instrs = +----------+----------+----------+----------+----------+ | instr3 | instr2 | instr0 | instr4 | instr1 | +----------+----------+----------+----------+----------+ instrs_idx = +-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+ | 2 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 3 | +-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

Indeed, in order to build the new shellcode correctly we have to execute the instruction in this order: instrs[2], instrs[4], instrs[1], instrs[0], and instrs[3].

However, if we want to swap instruction at i = 1, j = 2 it will give us:

instrs = +----------+----------+----------+----------+----------+ | instr3 | instr0 | instr2 | instr4 | instr1 | +----------+----------+----------+----------+----------+

but instrs_idx will NOT become:

+-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+ | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | +-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

What we need to do is to use the i_index, represented here by the number in instrX to swap values in instrs_idx: we do not swap instrs_idx[1] and instrs_idx[2], but instrs_idx[0] and instrs_idx[2]:

instrs_idx = +-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+ | 1 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | +-----+-----+-----+-----+-----+

It’s now time to compute jumps. Problem: we have to be sure that none of them has a distance equal to 0xeb… It’s what the routine in the while condition checks

We created another routine to compute jumps, in order to be able to call it as long as there are distances equal to 0xeb. The routine returns -1 in such case, and the value of the initial jump otherwise.

int set_jumps(Instr** p_instrs, int* p_instrs_idx, int p_nb_instrs){ int i, j, idx, idx1; unsigned char count; /** Set jumps BETWEEN "useful" instructions**/ for (i = 0; i < p_nb_instrs -1; i++){ count = 0; idx = p_instrs_idx[i]; //index of the current instruction in shuffled array idx1 = p_instrs_idx[i+1]; //index next instruction (to execute) in shuffled array if (idx1 > idx){ //move forward //start from the NEXT instruction IN THE ARRAY before reaching the next instruction TO EXECUTE for (j = idx+1; j < idx1; j++) count += (2 + p_instrs[j]->i_code_len); //+2 because jump instruction is 2-bytes long } else{ //move backward //start from CURRENT instruction until reaching the next instruction TO EXECUTE for (j = idx; j >= idx1; j--) count -= (2 + p_instrs[j]->i_code_len); //same reason for -2 } p_instrs[idx]->i_jump = count; if (count == 0xeb) return -1; //if the jump is equal to 0xeb (also jmp's opcode), return -1 } /** Set initial jump (reach the first "useful" instruction) **/ count = 0; for (i = 0; i < p_nb_instrs && i < p_instrs_idx[0]; i++) //instrs_idx[0] contains the index in the shuffled array of the first instruction to execute count += 2 + p_instrs[i]->i_code_len; return (count == 0xeb) ? -1 : count; }

In the first part of the routine, we compute jumps between instructions ( => not the initial one). The variables idx and idx1 represent the positions in the shuffled array of two instructions which are

consecutively executed. If idx1 is greater, it means the the next instruction to execute is placed after the current one in the shuffled array. Then, we start to count from the next instruction ad stop before reaching the expected instruction:

+----------+ | JMP -> 0 | +----------+ | instr5 | +----------+ | JMP -> x | +----------+ | instr0 | #idx +----------+ | JMP -> 1 | +----------+ ---+ start at idx+1 | instr2 | | +----------+ | | JMP -> 3 | | +----------+ | | instr3 | | +----------+ | | JMP -> 4 | | +----------+ <--+ stop before idx1 | instr1 | #idx1 +----------+ | JMP -> 2 | +----------+ | instr4 | +----------+ | JMP -> 5 | +----------+

However, if idx1 is smaller than idx (the next instuction to execute is placer before the current one), we have to move backward:

+----------+ | JMP -> 0 | +----------+ | instr5 | +----------+ | JMP -> x | +----------+ | instr0 | +----------+ | JMP -> 1 | +----------+ <----+ | instr2 | #idx1| +----------+ | | JMP -> 3 | | +----------+ | | instr3 | | +----------+ | | JMP -> 4 | | +----------+ | | instr1 | #idx | +----------+ | | JMP -> 2 | | +----------+ -----+ | instr4 | +----------+ | JMP -> 5 | +----------+

If a jump has a distance equal to 0xeb, the routine immediately returns -1 to re-shuffle. Otherwise, the second part of the routine will compute the distance for the initial jump.

It’s the same principle, even simpler since we know that we have to move forward until reaching the instruction instrs[instrs_idx[0]].

NB: Be careful, the value returned by set_jumps is an integer, but stored in count, an unsigned char, in mutate, that’s the reason why we compare against 0xff and not -1!

If set_jumps returns a value other than -1, it means that all distances are corrects, and the return value is used as follows (still in mutate, at the end):

... /** Build the new shellcode **/ *cursor++ = 0xeb; *cursor++ = count; //initial jump distance ...

We can now build the shellcode by appending code contained in each Instr:

... for (i = 0; i < nb_instr; i++){ instr = instrs[i]; for (j = 0; j < instr->i_code_len; j++){ *cursor = instr->i_code[j]; cursor++; // append "useful" instruction's code } *cursor++ = 0xeb; //jmp opcode *cursor++ = instr->i_jump; //distance to reach next instruction } ...

Once the new shellcode is written in cursor, it’s time to replace the cursor at the beginning and to copy the new shellcode somewhere in p_data. To know exactly where, we use the routine get_section and copy the new shellcode

at the given offset. We have to add 0x20 bytes because the shellcode is not placed at beginning of the section:

$ objdump -d -j .data metamorph metamorph: file format elf64-x86-64 Disassembly of section .data: 0000000000202000 <__data_start>: ... 0000000000202008 <__dso_handle>: 202008: 08 20 20 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 . ............. ... 0000000000202020 <shellcode>: 202020: eb 00 52 eb 00 57 eb 00 56 eb 00 68 2d 6c 00 00 ..R..W..V..h-l.. 202030: eb 00 68 2f 6c 73 00 eb 00 48 83 ec 04 eb 00 c7 ..h/ls...H...... 202040: 04 24 2f 62 69 6e eb 00 6a 00 eb 00 48 8d 7c 24 .$/bin..j...H.|$ 202050: 14 eb 00 57 eb 00 48 8d 7c 24 10 eb 00 57 eb 00 ...W..H.|$...W.. 202060: 48 89 e6 eb 00 ba 00 00 00 00 eb 00 b8 3b 00 00 H............;.. 202070: 00 eb 00 48 83 c4 2c eb 00 0f 05 eb 00 5e eb 00 ...H..,......^.. 202080: 5f eb 00 5a eb 00 _..Z..

It actually starts at 0x202020, 32 bytes after the beginning. Hence, we have

... /** Replace the shellcode in p_data**/ cursor -= SHELLCODE_SIZE; //replace the cursor at the beginning Elf64_Shdr *sec_hdr; if ((sec_hdr = get_section(p_data))) memcpy(p_data+sec_hdr->sh_offset + 0x20, cursor, SHELLCODE_SIZE); /** Destroy instructions **/ for (i = 0; i < nb_instr; i++) free(instrs[i]); free(instrs); free(cursor);

The routine mutate ends here, by modifying the shellcode in p_data (not the variable shellcode !). Because of the file overwriting, it will be the future shellcode !

We can now run the program and check its MD5:

Download source code here

Abstract The Thymeleaf release version 3.0.12 came with improvements in its sandboxed evaluation process, by restricting objects creations and static functio...

Abacus ERP is versions older than 2024.210.16036, 2023.205.15833, and 2022.105.15542 are affected by an authenticated arbitrary file read vulnerability. T...

It is a rainy Monday morning, and John is working from home, in his cozy apartment. He activated his VPN to access his business files, and everything is goin...

Intro When it comes to input sanitisation, who is responsible, the function or the caller ? Or both ? And if no one does, hoping that the other one will do t...

Intro After being tasked with auditing GLPI 10.0.12, for which I uncovered two unknown vulnerabilities (CVE-2024-27930 and CVE-2024-27937), I became really i...

Intro A few weeks ago, I discovered during an intrusion test two vulnerabilities affecting GLPI 10.0.12, that was the latest public version at this time. The...

I was recently tasked with auditing the application GLPI, a few days after its latest release (10.0.12 at the time of writing). The latter stands for Gestion...

I won’t insult you by explaining once again what JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) are, and how to attack them. A plethora of awesome articles exists on the Web, descri...

A few days ago, I published a blog post about PHP webshells, ending with a discussion about filters evasion by getting rid of the pattern $_. The latter is c...

A few thoughts about PHP webshells …

I remember this carpet, at the entrance of the Computer Science faculty, with this message There’s no place like 127.0.0.1/8. A joke that would create two ca...

TL;DR A few experiments about mixed managed/unmanaged assemblies. To begin with, we start by presenting a C# programme that hides a part of its payload in an...

It was a sunny and warm summer afternoon, and while normal people would rush to the beach, I decided to devote myself to one of my favourite activities: suff...

The reader should first take a look at the articles related to CVE-2023-3032 and CVE-2023-3033 that I published a few days ago to get more context.

This walkthrough presents another vulnerability discovered on the Mobatime web application (see CVE-2023-3032, same version 06.7.2022 affected). This vulnera...

Mobatime offers various time-related products, such as check-in solutions. In versions up to 06.7.2022, an arbitrary file upload allowed an authenticated use...

King-Avis is a Prestashop module developed by Webbax. In versions older than 17.3.15, the latter suffers from an authenticated path traversal, leading to loc...

Let’s render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, the exploit FuckFastCGI is not mine and is a brilliant one, bypassing open_basedir and disable_functio...

I have to admit, PHP is not my favourite, but such powerful language sometimes really amazes me. Two days ago, I found a bypass of the directive open_basedir...

PHP is a really powerful language, and as a wise man once said, with great power comes great responsibilities. There is nothing more frustrating than obtaini...

A few weeks ago, a good friend of mine asked me if it was possible to create such a program, as it could modify itself. After some thoughts, I answered that ...

In the previous article, I described how I wrote a simple polymorphic program. “Polymorphic” means that the program (the binary) changes its appearance every...

The malware presented in this blog post appeared on Google Play in 2016. I heard about it thanks to this article published on checkpoint.com. The malicious a...

Ransomwares are really interesting malwares because of their very specific purpose. Indeed, a ransomware will not necessarily try to be stealth or persistent...

A few days ago, I found this article about a malware targeting Sberbank, a big Russian bank. The app disguises itself as a web application, stealing in backg...

RuMMS is a malware targetting Russian users, distributed via websites as a file named mms.apk [1]. This article is inspired by this analysis made by FireEye ...

Could a 5-classes Android app be so harmful ? dsencrypt says “yes”…

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges_Part4.txt

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges_Part3.txt

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges_Part2.txt

~$ cat How_an_Android_app_could_escalate_its_privileges.txt

Even if the thesis introduces the extensions internals, and analyses the difference between mobile and desktop browsers in terms of likelihood, efficiency an...